- Tribal leaders consider granting the Colorado River its own legal rights.

- The move reflects a growing global “rights of nature” movement.

- Four U.S. states have already banned such personhood laws.

Friday, October 10, 2025 — The Arizona Republic’s Debra Utacia Krol reports that the Colorado River Indian Tribes (CRIT) are considering whether to recognize the 100-mile stretch of the Colorado River flowing through their reservation as a legal person. Tribal Chairwoman Amelia Flores said the idea has received broad support during a series of public hearings, including sessions in Phoenix for tribal members living off-reservation. Once the council finalizes the resolution, it would become tribal law—one that symbolically and legally reframes the river as a living entity rather than a mere water source.

reports that the Colorado River Indian Tribes (CRIT) are considering whether to recognize the 100-mile stretch of the Colorado River flowing through their reservation as a legal person. Tribal Chairwoman Amelia Flores said the idea has received broad support during a series of public hearings, including sessions in Phoenix for tribal members living off-reservation. Once the council finalizes the resolution, it would become tribal law—one that symbolically and legally reframes the river as a living entity rather than a mere water source.

According to the Republic, Flores and other tribal leaders describe the effort as part of a larger movement by Indigenous peoples to preserve and restore waterways. “We have to look at the river as a person,” Flores said, emphasizing that federal and state water negotiations often focus only on human users and not the river itself. Tribal officials argue that legal personhood could strengthen stewardship and remind outside agencies—the Bureau of Reclamation, the Department of the Interior, and others—that the Colorado has natural limits.

could strengthen stewardship and remind outside agencies—the Bureau of Reclamation, the Department of the Interior, and others—that the Colorado has natural limits.

Global and Tribal Precedents.

The legal concept of granting “personhood” to a natural feature traces back to legal scholar Christopher D. Stone, whose 1970s essay Should Trees Have Standing? argued that ecosystems should be able to defend themselves in court. Since then, Indigenous communities worldwide have advanced the idea.

New Zealand’s Maori tribes pioneered the modern version by securing recognition for the Whanganui River in 2017 through the Te Awa Tupua Act. In North America, the Yurok Tribe granted personhood to the Klamath River in 2019, establishing rights “to exist, flourish, and naturally evolve.” Two years later, Canada’s Magpie River received similar recognition. Comparable measures have emerged in India, Colombia, Bangladesh, and Brazil.

CRIT leaders say their proposal continues that trajectory. Tribal attorney Keith Drennan noted that although the 1928 Colorado River Compact excluded tribes from early negotiations, today’s Indigenous nations play an active role in basin management. “We find ourselves at a table we were never invited to,” he said, adding that tribal law must now protect what the compact overlooked.

States Moving in the Opposite Direction.

While Indigenous communities explore rights-of-nature laws, some U.S. states have gone the opposite direction, explicitly banning legal personhood for rivers, lakes, or ecosystems.

- Ohio (2019) – Ohio Rev. Code § 2305.011

declares that “nature or any ecosystem does not have standing” in court.

declares that “nature or any ecosystem does not have standing” in court. - Florida (2020) – Fla. Stat. § 403.412(9)(a)

bars local governments from granting legal rights to “a plant, an animal, a body of water, or any other part of the natural environment.”

bars local governments from granting legal rights to “a plant, an animal, a body of water, or any other part of the natural environment.” - Idaho (2022) – Idaho Code § 5-346

states that “environmental elements … shall not be granted personhood.”

states that “environmental elements … shall not be granted personhood.” - Utah (2024) – Utah Code Ann. § 63G-31-102

prohibits any governmental entity from granting legal personhood to non-human entities, explicitly including bodies of water.

prohibits any governmental entity from granting legal personhood to non-human entities, explicitly including bodies of water.

These state laws emerged largely in response to local ordinances that sought to recognize ecosystems as legal entities capable of defending their own rights in court.

FAQ

What does “river personhood” mean?

It is a legal and philosophical concept that grants a river or ecosystem certain rights—such as the right to exist, flow, and be free from pollution—similar to the way corporations have legal standing as “persons.”

Would the Colorado River be able to sue or own property?

Yes, theoretically. If enacted, the CRIT law would allow representatives (often called guardians) to act on the river’s behalf in legal matters.

Does this apply to the entire Colorado River?

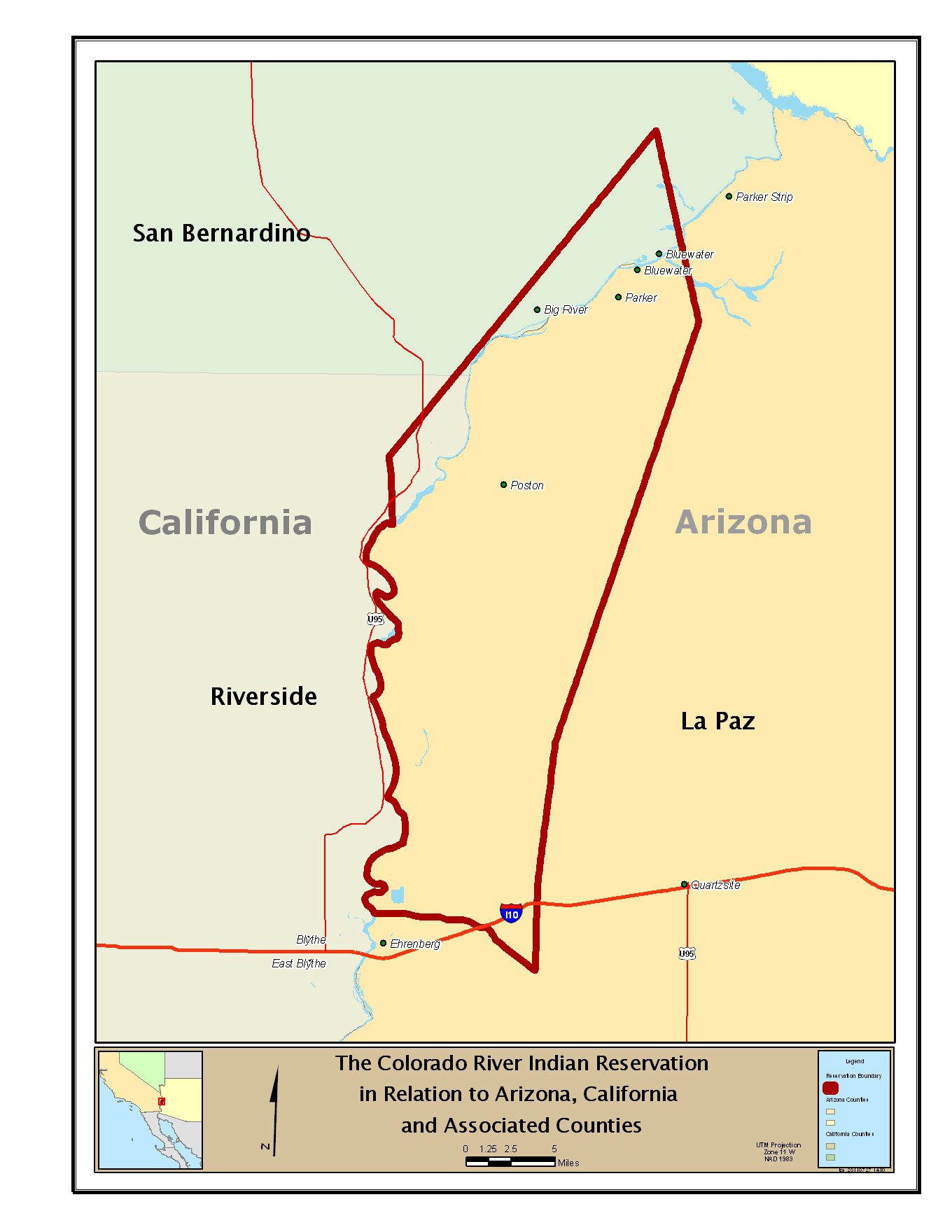

No. The proposed CRIT resolution would apply only to the portion of the river within tribal lands, roughly 100 miles through Arizona and California.

Why are some states banning these laws?

Opponents argue that granting legal standing to nature could invite excessive litigation or conflict with existing property rights. Supporters counter that traditional environmental laws have not been enough to protect ecosystems.

Is this connected to water-rights settlements or compacts?

Indirectly. Tribal leaders say that recognizing personhood complements, rather than replaces, ongoing water-rights frameworks by reframing how people relate to the river itself.