- Managed aquifer recharge offers benefits but remains difficult.

- Physical, economic, and legal barriers limit expansion.

- Overreliance on recharge can delay tougher groundwater reforms.

- Equity concerns are emerging as wealthier users dominate projects.

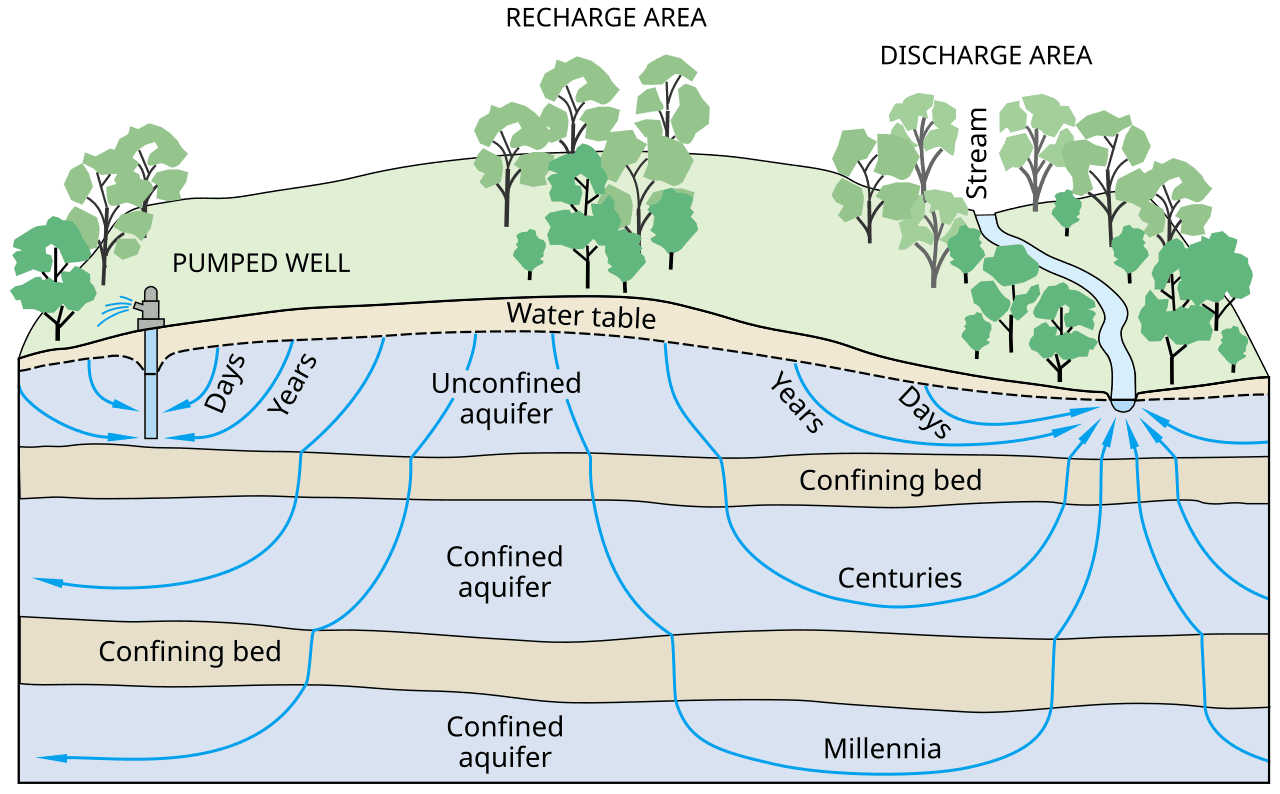

Thursday, November 13, 2025 — In recent years, interest in managed aquifer recharge has expanded across the United States. The research paper “Navigating the Growing Prospects and Growing Pains of Managed Aquifer Recharge ,” written by Dave Owen, Helen E. Dahlke, Andrew T. Fisher, Ellen Bruno, and Michael Kiparsky, explores both the potential and the pitfalls of relying on this approach. The authors note that managed aquifer recharge refers to the purposeful movement of surface water into groundwater basins so that it can later support water supply or environmental purposes.

,” written by Dave Owen, Helen E. Dahlke, Andrew T. Fisher, Ellen Bruno, and Michael Kiparsky, explores both the potential and the pitfalls of relying on this approach. The authors note that managed aquifer recharge refers to the purposeful movement of surface water into groundwater basins so that it can later support water supply or environmental purposes.

The study explains that the enthusiasm surrounding managed aquifer recharge is understandable. It can store surplus stormwater, reduce evaporation compared to surface reservoirs, and provide environmental benefits that are not always achievable with conventional infrastructure. As the authors write, programs in places such as Idaho’s Snake River Plain, central Arizona, and parts of California show that well-designed recharge can make a measurable difference in regional water budgets.

Yet, despite those encouraging examples, the researchers caution that the actual implementation of projects has lagged far behind expectations. Many regions still struggle to find suitable locations, build workable partnerships, secure water rights, and develop the monitoring systems needed for long-term success. According to the paper, these limitations make it risky for planners to rely heavily on projected recharge volumes when mapping out future water supply.

Technical and Physical Limitations.

One of the clearest themes in the paper is that managed aquifer recharge depends on suitable physical conditions. The authors explain that a project requires a dependable source of water, land through which water can infiltrate or be injected, and aquifers that are capable of storing and transmitting that water. Soil chemistry and water quality can also be major constraints, because recharge can mobilize contaminants or affect nearby drinking-water wells.

The researchers point out that these issues are often site-specific. A location with promising surface-water access may have incompatible geology, while a location with ideal geology may lack water of the right quality or quantity. These limitations help explain why recharge is not always a simple or inexpensive option.

Economic Uncertainty.

The paper highlights that project economics can be difficult for managers to evaluate. Recharge systems often operate intermittently, since they depend on unpredictable stormwater flows or episodic river surpluses. This makes it hard for project sponsors to calculate whether long-term benefits will offset capital costs.

The researchers also describe how successful recharge projects can unintentionally reduce incentives to conserve groundwater. When recharge raises water levels, pumping becomes cheaper. If not paired with extraction limits, these cost savings may encourage increased pumping, reducing the net benefit of the recharge effort.

Legal and Regulatory Obstacles.

The authors devote considerable attention to legal challenges, noting that regulatory oversight of groundwater remains inconsistent across the United States. Some states have no dedicated permitting system for recharge. Others have rules that make it difficult for project operators to retain the water they put underground. In places where groundwater is treated as a largely unregulated private property right, such as parts of Texas and Arizona, project sponsors may have no assurance that recharged water will be available when needed.

The researchers emphasize that strong legal frameworks are essential for protecting the public interest. Effective recharge programs rely on accurate accounting, reliable monitoring, and enforceable limits on groundwater extraction. Without these structures, the paper warns, recharge can easily underperform or fail altogether.

Risks of Over-Promising.

The study describes a pattern in which local agencies rely heavily on future recharge to meet long-term sustainability goals. The authors point out that California’s local groundwater plans often assume substantial volumes from projects that do not yet exist. In some regions, these assumptions are used to avoid or postpone reductions in groundwater pumping.

The researchers warn that if projected recharge volumes do not materialize, communities may face larger and more sudden restrictions later. In that sense, unverified expectations about recharge can create their own form of risk.

Equity Concerns.

Another key finding is the risk that recharge could deepen existing inequalities. The paper explains that managed aquifer recharge requires water rights, technical expertise, and capital—all resources more available to well-funded districts and large landowners. Because many of the new recharge projects benefit entities that already hold senior water rights, the authors note that recharge may strengthen the position of those who already have influence.

The researchers also caution that if the first entities to establish recharge projects claim access to available water, disadvantaged communities could be left with fewer options in the future.

Promising Policy Solutions.

The study concludes with several potential paths forward. The authors recommend:

Better information and reporting.

Improved data, standardized reporting formats, and broader access to project findings could help both public and private sponsors design more effective projects.

Stronger groundwater regulation.

The researchers emphasize that recharge alone cannot stabilize overdrafted aquifers. Pumping limits, monitoring requirements, and transparent reporting are needed to ensure that recharge produces lasting benefits.

Public-oriented recharge programs.

The authors highlight the role public agencies can play in ensuring that recharge benefits are shared. Publicly led programs may be better positioned to provide environmental benefits or support disadvantaged communities.

Allocating water for public purposes.

According to the paper, regulatory systems should require project operators to reserve a portion of recharged water to offset losses, support environmental flows, or help stabilize groundwater levels. This approach can ensure that publicly owned water provides a broader public good.

Conclusion.

The research by Dave Owen, Helen E. Dahlke, Andrew T. Fisher, Ellen Bruno, and Michael Kiparsky shows that managed aquifer recharge can play an important role in building more resilient water systems. At the same time, the authors caution that projects face significant physical, economic, legal, and equity challenges. The paper stresses that managed aquifer recharge must be paired with careful regulation, transparent accounting, and long-term planning. If these conditions are met, recharge can become one useful tool among many in addressing increasingly severe groundwater shortages.

Citation:

Owen, D., Dahlke, H.E., Fisher, A.T., Bruno, E. and Kiparsky, M. (2025), Navigating the Growing Prospects and Growing Pains of Managed Aquifer Recharge. Groundwater. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwat.70029

FAQ

What is managed aquifer recharge?

It is the intentional movement of surface water into an underground aquifer so that it can later support water supply or environmental needs.

Who conducted the study?

The research was conducted by Dave Owen, Helen E. Dahlke, Andrew T. Fisher, Ellen Bruno, and Michael Kiparsky. Their publication, Navigating the Growing Prospects and Growing Pains of Managed Aquifer Recharge, was released in 2025.

Why is managed aquifer recharge difficult to scale?

The study explains that many regions lack suitable physical conditions, dependable water supplies, clear legal frameworks, or economic incentives to sustain large projects.

Does managed aquifer recharge reduce the need for pumping restrictions?

According to the authors, no. Recharge can help stabilize groundwater, but long-term sustainability still requires limits on groundwater extraction.

Can recharge worsen inequality?

Yes. The paper notes that recharge projects often benefit well-funded entities with existing water rights, which can leave disadvantaged communities with fewer opportunities.

What policies could improve outcomes?

The researchers recommend stronger groundwater regulation, public-oriented recharge programs, better data collection, and requirements that some recharged water be reserved for public benefit.