- CRIT approved Colorado River personhood on November 6.

- The resolution directs leaders to protect the river’s needs.

- The action places CRIT alongside global rights-of-nature efforts.

Friday, November 14, 2025 — On November 6, 2025, the Colorado River Indian Tribes (CRIT) Tribal Council approved a resolution recognizing the Colorado River as a legal person under tribal law . The decision followed months of public input through meetings, written comments, and outreach efforts both on and off the reservation. Tribal officials described the action as a reflection of long-held cultural and spiritual beliefs about the river and a legal tool for its long-term protection.

. The decision followed months of public input through meetings, written comments, and outreach efforts both on and off the reservation. Tribal officials described the action as a reflection of long-held cultural and spiritual beliefs about the river and a legal tool for its long-term protection.

A Shift in Tribal Law.

Under the resolution, the Colorado River is recognized as having the right to be protected. The measure directs current and future Tribal Councils to consider the river’s needs when making decisions and provides a legal path for addressing harm caused by drought, climate change, and human use. According to the announcement, CRIT’s Attorney General will now develop provisions for inclusion in the tribal code, including the Water Code, to fully reflect the new status and lay out specific protections.

The resolution states in part that “there is no greater expression of sovereignty than protecting, stewarding, and securing for future generations what our Ancestors handed down to us,” adding that the personhood designation reflects the Tribe’s cultural, spiritual, and religious connection to the Colorado River “from the beginning of time through the end of time.”

Community Support and Leadership Statements.

Tribal leaders report broad support from members who participated in hearings on the reservation and in Phoenix. Chairwoman Amelia Flores said the new status provides a framework for concrete action. She explained that the river is central to CRIT identity and emphasized that long-term protection must accompany any expectation that CRIT help support Arizona’s economic future.

“Within Arizona, CRIT will be inevitably asked to help shoulder the burden of maintaining Arizona’s economy and way of life,” she said. “This must be a two-way street, however. At CRIT we are prepared to engage and be part of the solution for Arizona, but part of the solution is the long-term protection of our river.”

Growing Movement Among Indigenous Communities.

CRIT’s decision reflects a broader movement led by Indigenous communities around the world to recognize natural features as legal persons. The modern version emerged from the work of legal scholar Christopher D. Stone, whose 1970s essay argued that ecosystems should have standing in court. Over the past decade, several Indigenous nations and governments have adopted similar measures.

reflects a broader movement led by Indigenous communities around the world to recognize natural features as legal persons. The modern version emerged from the work of legal scholar Christopher D. Stone, whose 1970s essay argued that ecosystems should have standing in court. Over the past decade, several Indigenous nations and governments have adopted similar measures.

New Zealand’s Maori tribes secured legal recognition for the Whanganui River in 2017. The Yurok Tribe recognized the personhood of the Klamath River in 2019, and the Magpie River in Canada received the same treatment in 2021. Comparable actions have appeared in India, Colombia, Bangladesh, and Brazil.

CRIT leaders say their decision continues this global trajectory. Tribal attorney Keith Drennan has noted that while tribes were excluded from the 1928 Colorado River Compact, Indigenous nations now participate actively in basin management. He said tribal law must protect what the original compact omitted.

State-Level Restrictions Elsewhere.

As some Indigenous communities expand rights-of-nature protections, several states have moved in the opposite direction. In recent years, Ohio, Florida, Idaho, and Utah have passed laws prohibiting legal personhood for rivers, lakes, and other ecosystems. These laws emerged in response to local efforts that sought to recognize nature as a rights-bearing entity capable of defending itself in court.

CRIT’s action does not conflict with state statutes because the decision is made under tribal law and applies to the portion of the Colorado River that flows through the reservation. Still, it represents a significant development at a time when the river faces chronic drought, declining flows, and increasing pressure from both human use and climate conditions.

What Comes Next.

Tribal attorneys will now draft specific legal provisions for Tribal Council review. Once adopted, those provisions would determine how personhood functions within the tribal legal system, what remedies are available when harm occurs, and how the river’s interests are considered in governance decisions.

The recognition does not change existing federal, state, or interstate water allocations. However, it adds a new legal and cultural dimension to ongoing water negotiations across the Colorado River Basin. CRIT leaders have said the measure strengthens stewardship and reinforces the idea that the river itself has needs that must be considered as the region prepares for future shortages.

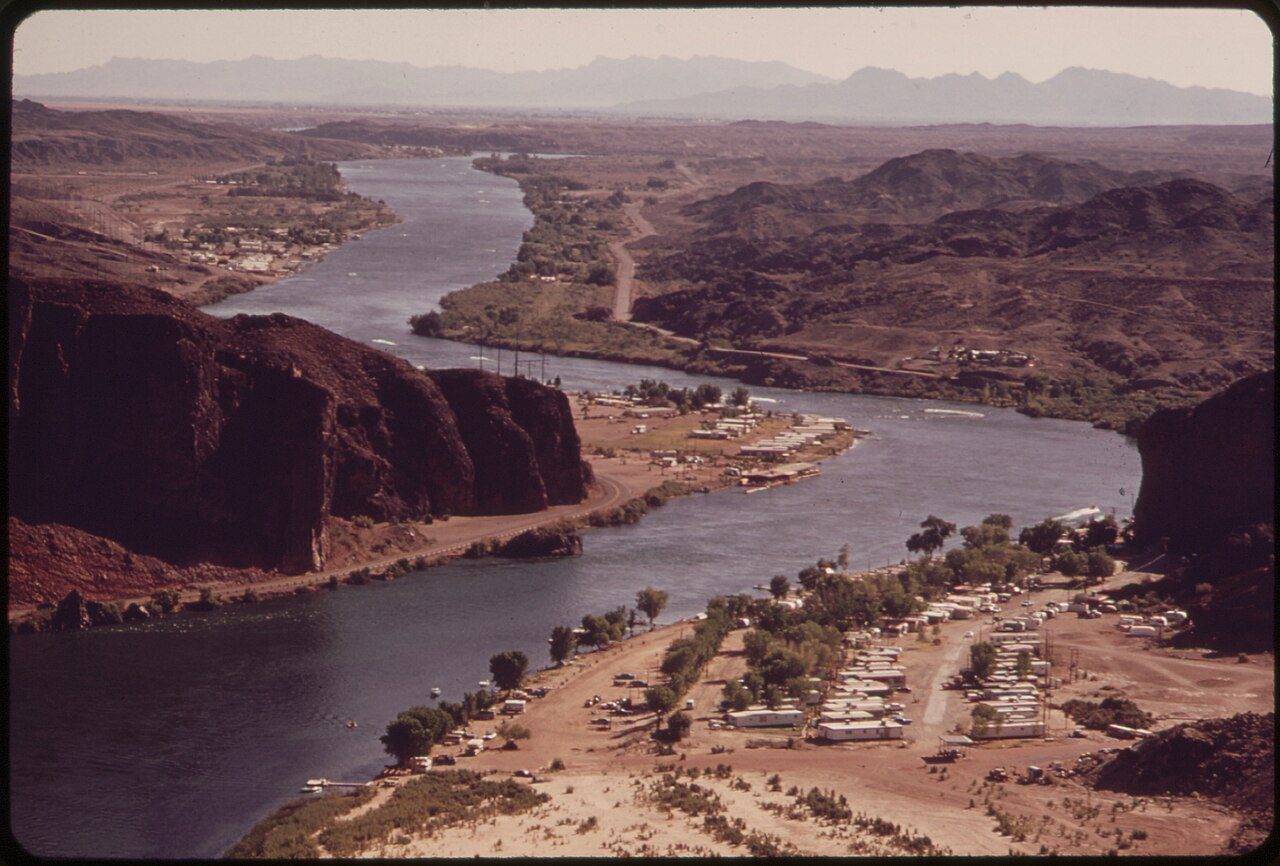

Image: Public domain image from the Environmental Protection Agency taken in May 1972. “THE COLORADO RIVER BELOW PARKER DAM. ARIZONA IS ON THE LEFT; CALIFORNIA, ON THE RIGHT OF THE RIVER.”

from the Environmental Protection Agency taken in May 1972. “THE COLORADO RIVER BELOW PARKER DAM. ARIZONA IS ON THE LEFT; CALIFORNIA, ON THE RIGHT OF THE RIVER.”

Frequently Asked Questions

What did CRIT decide on November 6? The Tribal Council approved a resolution recognizing the Colorado River as a legal person under tribal law. This status requires future decisions to account for the river’s needs and authorizes legal protections for the river.

Does river personhood change CRIT’s water rights or the Colorado River Compact? No. The recognition does not alter CRIT’s existing water rights or any provisions of the Colorado River Compact. It functions within tribal law and does not modify interstate agreements.

How will this status be implemented? CRIT’s Attorney General is drafting provisions for the tribal code, including the Water Code. These provisions will outline how personhood operates in practice and what protections the river may receive.

Is CRIT the first to do this? CRIT is the first community to recognize personhood for the Colorado River. Other Indigenous nations worldwide have taken similar actions for rivers and ecosystems.

Does this affect state laws prohibiting personhood for natural features? No. The decision applies to tribal lands and is made under tribal sovereignty. It does not override state statutes in Arizona or elsewhere.

Why is this significant now? The Colorado River faces long-term drought, declining flows, and increasing demand. Tribal leaders say the river’s protection is essential for ecological health and cultural continuity.

Will this impact future water negotiations? While the recognition does not change legal allocations, it may influence how CRIT engages with state and federal negotiators by reinforcing the river’s ecological needs in policy discussions.