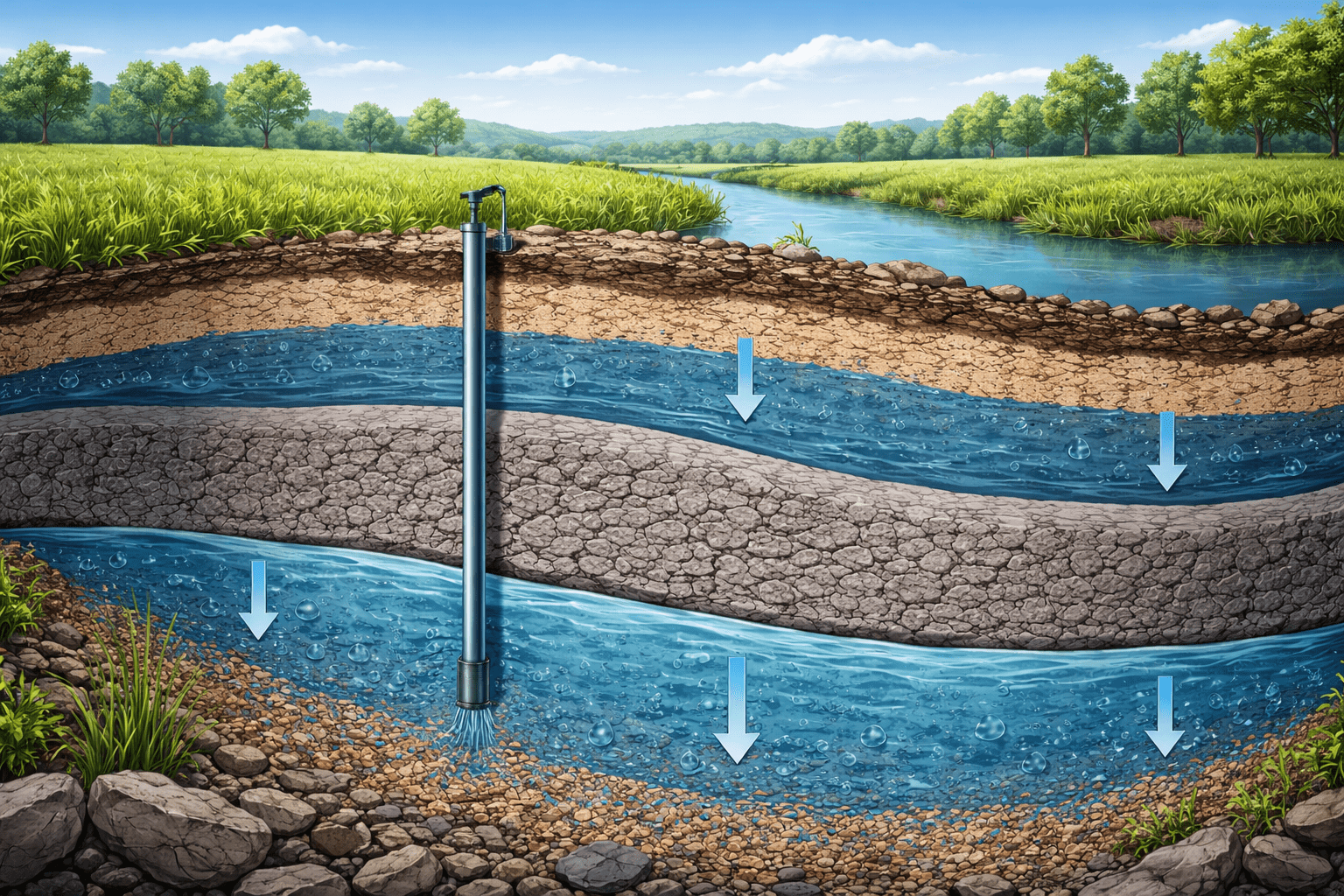

- Aquitards are low-permeability layers that slow groundwater movement and help block contaminants.

- New research shows aquitards are complex, uneven, and sometimes allow flow in unexpected directions.

- These layers affect water quality, land subsidence, and long-term water management decisions.

- Understanding aquitards is becoming more important as groundwater use intensifies.

Wednesday, December 31, 2025 — Groundwater discussions often focus on aquifers, the underground layers that readily store and transmit water. Less attention is paid to aquitards, the low-permeability layers of clay, silt, or fine-grained sediment that lie above, below, or between aquifers. A guest editorial published December 26, 2025 , in the journal Groundwater by Madeline Gotkowitz and David Hart explains why that oversight matters and how aquitards quietly shape groundwater systems in ways that affect water supply, contamination, and land stability.

, in the journal Groundwater by Madeline Gotkowitz and David Hart explains why that oversight matters and how aquitards quietly shape groundwater systems in ways that affect water supply, contamination, and land stability.

Aquitards are commonly described as confining layers because they restrict groundwater movement. In practice, however, they are rarely simple or uniform. Their thickness, composition, and internal structure can vary widely across a region. Many contain fractures, thin sandy lenses, or eroded openings that allow some groundwater to pass through. These features complicate predictions about how water and contaminants move underground.

Not Just Barriers, But Complex Pathways.

The editorial highlights research that challenges the idea of aquitards as solid barriers. One paper in the special issue introduces the term “aquitardifer” to describe low-permeability formations that restrict flow in some directions while transmitting water in others. This directional behavior helps explain why some production wells successfully draw water from formations long labeled as confining layers.

introduces the term “aquitardifer” to describe low-permeability formations that restrict flow in some directions while transmitting water in others. This directional behavior helps explain why some production wells successfully draw water from formations long labeled as confining layers.

Such findings matter for groundwater modeling and well design. When aquitards are oversimplified, pumping impacts can be misunderstood, leading to inaccurate predictions of drawdown, recharge timing, or contaminant spread.

Teaching and Studying the Overlooked Layers.

According to the authors, aquitards are not consistently emphasized in hydrogeology education. As a result, new professionals may struggle to recognize groundwater systems where these layers play a central role. The special issue includes examples of laboratory exercises and field measurements designed to help students develop practical intuition about aquitards and their influence on flow systems.

Research methods commonly used to study aquifer heterogeneity are also being adapted to better understand aquitards. Modeling studies show how pumping tests behave differently when low-permeability layers are part of the system, improving interpretation of real-world data.

Water Quality and Public Health Connections.

Aquitards also influence groundwater chemistry. Fine-grained layers can affect levels of arsenic, iron, manganese, and nitrate in drinking water wells. Studies summarized in the editorial examine how groundwater moves through sequences of aquifers and aquitards, shaping water quality in public supply systems. These findings have direct implications for monitoring, treatment, and well placement decisions.

Stability, Subsidence, and Coastal Risks.

Beyond water supply and quality, aquitards play a role in land stability. The editorial discusses research linking changes in aquitard chemistry to increased landslide risk, particularly in marine clays affected by modern recharge. Other studies focus on land subsidence, a global hazard tied to groundwater extraction. Compaction of fine-grained sediments can lower land surfaces, worsen flooding, and damage infrastructure such as roads, pipelines, and building foundations.

In coastal regions, simulations show that seawater intrusion can trigger osmotic processes within aquitards, contributing to subsidence. These findings are especially relevant for low-lying communities already facing sea level rise.

Implications for Groundwater Management.

Taken together, the research presented in the special issue underscores that aquitards are not passive background features. They actively shape groundwater flow, contaminant transport, water quality, and land stability. As groundwater use intensifies and climate variability places new stress on water systems, understanding these low-permeability layers becomes increasingly important for sound planning and risk management.

Citation.

Gotkowitz, M. and Hart, D. (2025), Aquitards in Groundwater Systems: Groundwater Special Issue. Groundwater. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwat.70044

Frequently Asked Questions

What is an aquitard in simple terms?

An aquitard is a layer of underground material, often clay or silt, that slows the movement of groundwater but does not completely stop it.

How is an aquitard different from an aquifer?

An aquifer readily stores and transmits groundwater, while an aquitard has much lower permeability and restricts water movement.

Can water move through an aquitard?

Yes. Many aquitards contain fractures or thin permeable zones that allow limited groundwater flow, sometimes in specific directions.

Why do aquitards matter for drinking water?

They can limit or redirect contaminant movement and influence the chemistry of water reaching public supply wells.

How are aquitards linked to land subsidence?

When groundwater levels drop, fine-grained sediments in aquitards can compact, causing the land surface to sink and increasing flood and infrastructure risks.

Who authored the editorial summarized here?

The guest editorial was written by Madeline Gotkowitz of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and David Hart of the Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey, and published December 26, 2025, in Groundwater, a journal of the National Ground Water Association.